Here’s the good news: forests managed by Indigenous people in the Amazon region served as life-saving carbon sinks from 2001-21, removing the equivalent of the UK’s annual fossil fuel emissions each year, according to a new study by the World Resources Institute. WRI’s data show similar success for forests managed by Indigenous, Afro-descent and other peasant communities around the world. Collectively-held forests in Mexico and the Philippines, for example, sequestered the equivalent of the fossil fuel emissions of Romania.

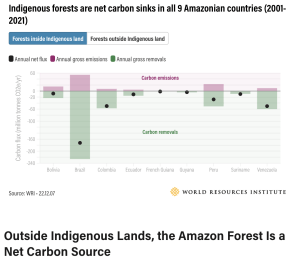

World Resources Institute graph documenting how Amazonian forests managed by Indigenous people sequester far more carbon than they emit.

And here’s the bad: “ Deforestation, degradation and other disturbances, however, have already turned some of the world’s most iconic forests into carbon sources and threaten to convert others,” the WRI report continues. “Over the past 40-50 years, an estimated 17% of Amazonian forest has been lost, of which over four-fifths was converted to agricultural land, mainly pastures. Scientists estimate that deforesting 20% of the Amazon could push it past a tipping point, triggering a large-scale dieback that would release more than 90 billion tonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere (approximately 2.5 times greater than annual global fossil fuel emissions).”

Do we see forests as something sentimental, or do we recognize the ecological services they provide as essential to our very survival, and price them accordingly? The New York Times reported Jan. 15 (“Ecuador’s Bid to Curb Drilling is Now Reversed”) that a new drilling platform has been completed near Indigenous communities in Ecuador’s Yasuní National Forest. The nation’s 2007 plan to keep oil reserves in the ground under this rainforest failed because donor nations provided only a pittance towards the $3.6 billion needed to replace oil revenues in an economy where a fourth of the children are malnourished.

We share more data later in this article, showing why it matters who manages forests and how we can help conservation win. This is an emergency Rotarians are perfectly positioned to meet. We can strengthen the ability of local communities to withstand the immense forces driving deforestation.

Here’s why Rotary can help. Our clubs are local and enduring. Our ethics require us to strive for fair and beneficial outcomes for all. We use our skills and networks to advocate, educate, and equip our communities. Through Rotary’s generational campaign to end polio we’ve discovered that we have the grit to succeed in a daunting long-term quest that requires deep empathy for local cultures. We know how to give and raise money for practical solutions to humanitarian crises.

ESRAG’s articles this month showcase Rotarians who are working to restore and sustain biodiversity, especially in forests. The work goes far beyond planting trees to include capacity-building: natural resource management skills, advocacy, building sustainable new livelihoods, and partnerships that transcend social divides. As with polio eradication, we are learning from both mistakes and successes, and adapting accordingly.

This month, you’ll read about how Filippinos on the island of Negros are starting to reverse 150 years of massive deforestation by a thirty-year alliance between grassroots organizations, governments, universities, business, and civil society, including a local Rotary Club’s foundation. Read the rousing call to action of RYLA students who met in January at San Lorenzo School in Laguna Province, and how they are joining forces with Philippine Rotarians and Rotaractors to restore watershed forests and coastal mangroves.

A coalition of 16 peoples’ organizations are restoring the watersheds and biodiversity of Mt. Tallis/Twin Lakes on the Philippine island of Negros through monitoring, advocacy, and agroforestry, aided by a local Rotary Club’s foundation. Photo by Apolinario Cariño for UNDP Equator Initiative case study on Penagmannak, 2006 Equator Prize winner.

Half way round the globe we shine a joyful spotlight on Europe, where all 18 of France’s District Governors carried out a campaign in 2021-22 to reverse the disastrous attrition of bees by buying rose bushes at wholesale prices, selling them at a reasonable markup, and using the proceeds to provide thousands of hives, bee hotels, and tons of seeds for pollinator-friendly flowering plants across France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Monaco. Learn about their canny PR campaign that generated over 200 news stories on this opportunity to restore pollinator populations. Then, get your DGs to replicate this great project!

Mapping assets and hotspots: As you dive in, we’d like to share some big-picture resources. The World Resources Institute study draws on increasingly detailed data on carbon sinks and sources around the world. These include the maps of 21st century forest carbon fluxes reported in Nature Climate Change, Jan. 21, 2021 by Harris, et al. These document the greenhouse gas emissions and removals of forests globally. You would need to pay $32 US for access to this study or $99 to subscribe to the journal, but the abstract page includes several open-access studies using their data on China, the US, and Africa.

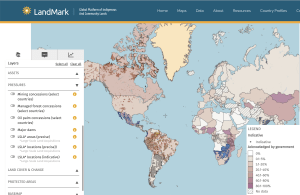

In addition, you can study maps of Indigenous- and community-managed land generated by the growing database of LandMark. This interactive website allows you to filter maps by a variety of characteristics including the security of land tenure, and pressures such as mining, forest, and oil palm concessions, major dams, and large-scale land acquisitions.

LandMark map showing filters you can apply to map pressures on Indigenous forests

More trends, and what we can do about it. Here are additional important insights and policy implications from the WRI study linked at the start of this article. “A growing body of research shows that lands managed by Indigenous people — both through legal title and informal, customary ownership — have lower deforestation rates than similar lands managed by other forest users. Lands legally held or titled to Indigenous people exhibit even lower deforestation rates than untitled Indigenous lands, underscoring the importance of tenure security to sustainable land management,” the WRI reports.

“Forests in the Amazon bioregion outside Indigenous lands were collectively a net carbon source between 2001 and 2021. These forests emitted 1.3 billion tonnes CO2e/year due to forest loss and removed about 1 billion tonnes CO2/year, making them a net source…equivalent to the annual fossil fuel emissions from France.

“Forest loss in Brazil, which comprises three-quarters of total regional loss, is the driving factor. Forest loss outside Indigenous lands in the Brazilian Amazon was such a significant source of carbon it counteracted the effects of the other Amazonian countries, which were either small carbon sinks or carbon sources. In Brazil, forests outside Indigenous lands are rapidly being lost to commercial farming and cattle ranching, extractive industries, infrastructure and other developments.”

The WRI’s policy recommendations include:

- Count the carbon sequestration of community forests as part of countries’ Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) under the UN Climate Accord. “In Brazil, Colombia, Peru and Mexico, for example, Indigenous forests sequester emissions equivalent to an average 30% of their countries’ national emissions-reduction pledges… The climate community — including international negotiators, national policymakers, donors and civil society leaders — should recognize the mitigation contributions of community forests.”

- Secure and protect community lands: “Securing community lands is a low-cost, high-benefit investment and a cost-effective carbon mitigation measure when compared to other carbon capture and storage approaches. Governments should support communities in their efforts to protect and sustainably manage their land.”

- Increase development assistance – both government and private – for projects supporting community forest management in tropical countries. WRI reports that less than 1% of official development assistance for climate change goes into community forest management. “Should community forests be degraded or lost, large stocks of carbon would be released into the atmosphere and the lands would no longer be able to sequester the same amount of carbon. Governments and donors should channel more financial resources to communities and their organizations, recognizing that they’re some of the world’s best forest protectors,” they write.

Rotarians can draw on these points in advocacy with our local, regional, and national governments, at the UN Biodiversity and Climate conferences (COP) and as shareholders and donors. We can also use these data to guide community needs assessment, asset mapping, project design, and Rotary global and district grant proposals.