By Ariel Miller, ESRAG Newsletter Editor

For over thirty years, Brian Braginton-Smith has been urging the United States to change course to prevent climate calamity. Working from the storm-battered Massachusetts coast where he grew up, this American Rotarian has developed a comprehensive plan for resiliency, carbon capture, and circular economy.

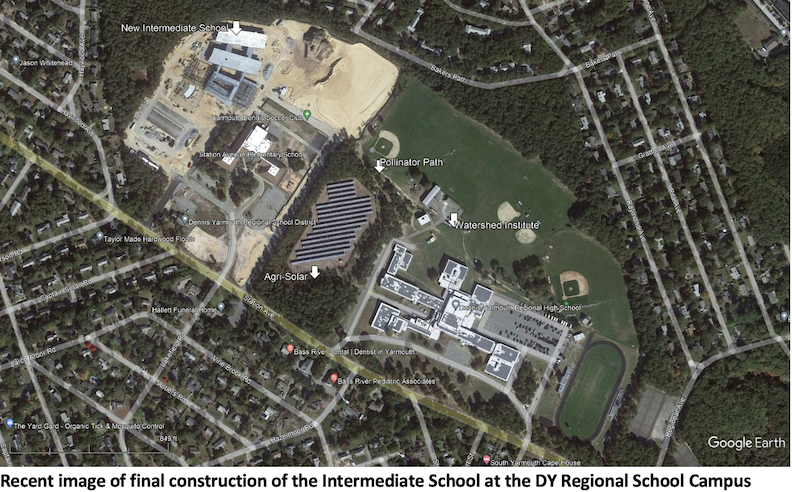

Teaching circular economy hands-on: the campus of Dennis-Yarmouth Intermediate School

Despite achievements including catalyzing offshore wind generation off Cape Cod, he couldn’t get policy-makers to consider wholistic solutions to the looming crisis. Now, all of a sudden, everyone’s paying attention: the US Government, the State of Massachusetts, a Norwegian firm with a breakthrough solution for rechargeable batteries, and the Dennis-Yarmouth Regional Schools that educate the children of Cape Cod.

The result: this school district will become the heart and engine for teaching circular economy and developing the regional workforce essential to its success. Rotarians will need to help lead this transformation, and ESRAG’s network will help get the roadmap to others worldwide who can replicate it.

Cape Cod proving ground for a sustainable economy

The Cape Cod Watershed Institute’s template for Connected Community

Braginton-Smith has been awarded US $1.37 million in funding from the State of Massachusetts to create the Cape Cod Watershed Institute as a collaboration of the Lewis Bay Research Center which he leads, the Dennis-Yarmouth Regional Schools led by Superintendent Carol Woodbury, and the Cape Cod Collaborative led by Phil Morris. All three are members of the Yarmouth Rotary Club.

Centered on the schools, whose infrastructure will become NetZero, the Cape Cod Watershed Institute will provide hands-on learning for students and workers on these new, sustainable systems and the skills needed to construct and maintain them.

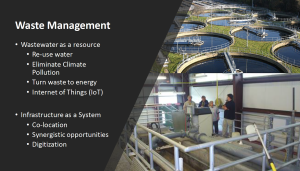

The strategy, which Braginton-Smith calls Connected Communities, an provides off-grid microgrid based on renewable energy, recycling of wastewater and other resources, and integrated micro-grid systems management using the Internet of Things. Students and workers will learn in “Newton Room” STEM-based green tech classrooms and on-campus or nearby NetZero infrastructure including building-integrated renewable energy, wastewater treatment re-use systems as an alternative water resource, and urban agriculture.

It will also include onsite learning opportunities at the Sandwich Green Community, with 144 units of desperately-needed affordable housing, solar-powered electricity and farming, energy storage, and advanced recycling.

Farming systems for students and trainees to learn sustainable practice.desperately-needed affordable housing, solar powered electricity and farming, energy storage, and advanced recycling.

“The vision is to create a platform where folks can learn about our watersheds and ecosystems while also actually seeing first-hand what it will take to bring about more sustainable, inclusive, and resilient communities,” Braginton-Smith explains. This is “all related to a transition from a linear to a circular economy for our species.”

A member of ESRAG’s Technical Cadre of experts, he sees this as “as a model to be shared and replicated globally to deal with the very real crisis that is upon every community everywhere, from housing to jobs, and – most importantly – repairing damage already done.” Rotarian Jeff Smith, who’s leading a multi-district strategy for green economic revival in New York State, is in close contact with Braginton-Smith, eager to apply the lessons from Cape Cod.

What changed?

“Over the past 40 years, the biggest dilemma was the institutional mindset,” says Braginton-Smith. “We have to show people there is a different way, and that they can make a difference. People feel fatalistic and helpless.”

Fourteen years ago, he pitched the idea of launching hands-on sustainability education to the Dennis-Yarmouth Schools. No luck. Then, right before the Covid pandemic, Superintendent Woodbury called him and explained that she, her second-in-command Ken Jenks, and DY High School Principal Dr. Paul Funk had been discussing the plan.

She said she had been re-reading his proposal, and that, “based on what is going on, we have to make this happen.” That started the momentum for the Cape Cod Watershed Institute. State Senator Julian Cyr, who represents half of the Cape Cod and islands region, agreed. With support from the rest of the Cape Delegation, he facilitated an appropriation. That bore fruit in an earmark and bond in the state’s 2023 economic development bond bill, for $1.37 million.

The money will expand the existing green infrastructure of the schools, as well as education and training facilities on and offshore. Work and learning at these sites will help restore Cape Cod’s fragile watersheds and sole source aquafer, while also solving a severe housing crisis and strengthening an economy precariously based on tourism.

The next seismic change was in Rotary. Braginton-Smith had joined the Interact Club as a student at Dennis-Yarmouth High School over 50 years ago. He was captivated by the idea of community service, but he didn’t realize that Rotary could be a lifelong adventure. When he joined Rotary years later, he was still a lonely voice whenever he brought up the climate crisis. “The Yarmouth Rotary Club and RI dismissed environmental concerns as ‘a political issue,’” he recalls wistfully.

“That was right up until two years ago, when I discovered that environmental sustainability was something Rotary was committed to as the most important cause on the planet. I began to get motivated and was made to feel like part of the team,” he says. Throughout the pandemic, ESRAG seminars and conferences via Zoom enabled the rapid growth of a network of environmentally-concerned, multi-skilled Rotarians. “All of a sudden people around the world began to get connected and work together on the climate: Oh, my God!” Braginton-Smith exclaims.

Then Joe Biden was elected U.S. President and succeeded in getting Congress to pass landmark legislation: the Infrastructure Bill, the CHIPS Act, and the Inflation Reduction Act, all launching unprecedented investments in climate solutions as a national priority.

Springboard for innovation: trust rooted in decades of collaboration

Braginton-Smith had worked for years with key federal agencies including NOAA (the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) and the Departments of Energy and Commerce. Last fall he was invited by the US Government to participate at the Global Clean Energy Action Forum in Pittsburgh. There he teamed up with the Norwegian firm Beyonder to demonstrate a breakthrough lithium-ion capacitor made with renewable energy and sawdust-based biochar. Using biomass in the batteries is a form of carbon capture from what would otherwise be waste wood. Biochar has many benefits and is incorporated in several ways in the NetZero Campus, from final water polishing to regeneratng soil for sustainable agriculture.

“The batteries can be fully charged in two minutes and recharged up to 100,000 times, thus reducing the need for frequent replacement of batteries, and the technology eliminates the threat of fires,” the exhibitors explained. “Beyonder’s LiC is a better fit for many purposes compared to commercially-available Li-ion batteries, and solves challenges not addressed in today’s batteries in high-power applications.” The Beyonder battery pack “enables us to solve several of the current energy challenges, e.g., allowing renewable power into electricity grids around the globe, electrifying heavy duty vehicles” on land or sea, and providing “solutions for fast and powerful charging infrastructure. “

The economic development potential for this technology is huge, given the major bottlenecks in supply chains for rechargeable batteries, the range and recharging issues hampering green transportation, and the challenges of integrating renewable energy generation with existing grids. The US Departments of Agriculture, Commerce, and Energy are eager to mobilize its potential for generating new farm income and international trade. The next step is for the Cape Cod Watershed to demonstrate the production of the biochar for the capacitors, which reduces the need for strategic minerals.

Rooted in Rotary ethics and action

This project brings Braginton-Smith back to his young self, yearning as a student for hands-on learning he could apply directly to improving people’s lives. Through the Cape Cod Watershed Institute, “we can teach the kids the vision and the ethics,” he says. “The best thing that happened to me was finding Rotary. I was always trying to figure out how to live in a way that I didn’t have to keep proving what was true: that we need to be doing things to better our society.

“Every community has a school. Many have colleges and universities. If you have a campus already there, it has to be looked upon as a community benefit, a community investment. Now we can align them to bring about a paradigm shift.

“Every community has a school. Many have colleges and universities. If you have a campus already there, it has to be looked upon as a community benefit, a community investment. Now we can align them to bring about a paradigm shift.

“If you show kids that water being used in our urban farming is properly recycled wastewater, they are not going to go to Town Meeting as adults and approve something that is a dirty way to go. Vision isn’t something that only Tesla is gifted with: it’s something that everybody’s got. The key is like-minded people.

“Our calling,” he adds, “is to create hope in the world.”