by Ariel Miller, ESRAG Newsletter Editor

Families meeting with Rotarians to discuss the water system they will be gaining through a $1 million global grant project in Honduras. Photo provided by Clayton Lee.

“I have a dream on how Rotary can achieve impact and together we can change the future of third world countries. Can we talk next week and hopefully change lives?”

Clayton Lee, Sacramento Rotary’s International Service Chair, sent this irresistible invitation in response to ESRAG’s December newsletter. Working with World Vision and Honduran communities on an $800,000 water and sanitation project, he wanted to know if ESRAG is also partnering with major global NGOs.

“Most people in the world have not heard of Rotary yet, but 100% of the developing world knows about World Vision,” he noted. “By collaborating with World Vision, Rotarians will have vastly more impact. It would be great to follow up with other global grant projects once the WASH projects are done, to advance multiple Rotary Areas of Focus like environmental sustainability and community economic development as we strive to meet the Sustainable Development Goals deadlines.”

Lee told me that soul-searching conversations were already under way on the future direction of Rotary’s water, sanitation, and hygiene work, and sent the links to register. I listened to Zoom calls Dec. 12th and 14th as Erica Gwynn, Rotary’s WASH Program Manager, facilitated discussions on whether Rotary’s WASH investment of $185 million to date has had lasting impact, and the changes we need to make to ensure that future work achieves the hoped-for good.

That same week I experienced a revelatory conversation with the world’s leading social entrepreneur on public toilets, Jack Sim of Singapore, who had joined Gwynn’s Zoom call and challenged Rotarians to try advocacy. To galvanize us, he described how his World Toilet Organization (WTO) catalyzed a pivotal legislative vote in Brazil in 2019 that opened the door to huge investments in sanitation. In our subsequent chat, he offered two powerful metaphors: think of poverty as a Swiss watch taken apart, its components scattered across a table, and prosperity as a thriving forest.

Can we use sanitation as a tool to transform poverty into prosperity? Here’s what I learned from Gwynn, Sim, and Lee.

The Rotary Foundation’s Erica Gwynn is urging Rotary WASH advocates to go beyond our longstanding focus on funding infrastructure.

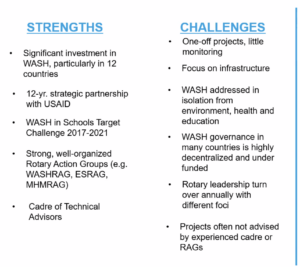

Rotary WASH strengths and weaknesses: a slide shared by Erica Gwynn during December’s Zoom discussions.

She challenged us to figure out how we can contribute to strengthening the other systems essential to WASH:

- Public policy

- Connecting and coordinating institutions

- Planning

- Finance

- Monitoring

- Regulation and accountability

- Water resources management, and

- Learning and adaptation.

All of these are equally vital to the success of other environmental projects.

And here is the amazing story of the WTO’s advocacy in Brazil.

In 2019, the Brazilian government was operating 94% of the nation’s sewage treatment systems but they were woefully inadequate. Half of the nation’s sewage sludge was discharged untreated into its lakes and rivers. The sanitation NGO Instituto Trata Brasil and the water company SABESP were trying to persuade the Brazilian government to change national law to allow public-private partnerships.

The WTO teamed up with Trata to hold its annual World Toilet Summit in Sao Paolo that year. Together they attended a Senate hearing to brief the legislators on the enormous losses which the Brazilian economy was incurring because half of the Brazilian population was struggling to survive without safe sanitation.

“You don’t have the money to solve this,” Sim says they told the Senators, “but you can change the law to allow companies to come in. Your unions will resist, but you need to persevere. Health, tourism, and land value will increase. You will lose some union votes, but will win a lot of votes from ordinary people.”

The legislature passed the authorizing legislation in June of 2020. By 2023, $15 billion in public and private investment – much of it from overseas – had already flowed in, transforming the sanitary systems of Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paolo. Sim hopes that a total of $150 billion will be committed by 2035 to deliver sanitation to the entire population of Brazil.

Rotarians: are you serious about ending poverty?

Here is Sim’s central point: sanitation is a passport out of poverty. “Cleanliness is an asset of a community’s and a country’s competitiveness,” he says. Earlier this year he visited a favela in Sao Paolo where civic pride and conditions have improved dramatically. “When people are healthy, they are more productive, they want to buy clean water and have sanitation,” he says. “They don’t want to live next to untreated sewage. The vendors contract to make the plants operate well. Then the system can start to make money.”

The secret is to pull together every sector who can also benefit from improved community health and wealth. The WTO has a chart of stakeholder incentives, listing what they stand to gain from investing in effective sanitation. These stakeholders include local communities, politicians, corporations, funders, investors, technologists, academics, and media. Rotarians fit under the category of NGOs, but Gwynn, Lee and Sim all agree we’ll accomplish little if we stay in our silo, congratulating ourselves on little projects.

“You have a limited life span,” Sim says. “Do you want to save a few people or save millions with the same amount of time and effort?”

Sim and Lee speak from direct experience on how a small NGO can leverage massively more impact by teaming up with other investors with the same goal. “You can’t get past the door with World Vision, the Gates Foundation, or the Hilton Foundation unless you have a project of scale,” says Lee.

Joining a project with big impact is hugely motivating for local clubs. For example, “USAID and Rotary were collaborating on a water project in Uganda,” he reports. “They wanted clubs to put in 20% of the cost. The large club in our district (5180) challenged the smaller clubs to work together to match the contribution of the large club.” It took just two weeks to reach the fundraising goal because the small clubs were thrilled to see their contributions would leverage a 20-fold match from the large club, district funds, the Rotary Global Grant, and USAID.

“Our global grant project for Honduras was over-subscribed because of the match” from the District, The Rotary Foundation, and World Vision, Lee reports. “World Vision is the largest NGO in the world, actively involved with water in 100 nations. When it comes to water and everything else they do, they make sure they are doing things right,” he adds. “They update and revise. They have in-country staff, and they start with the end of the road: the poorest of the poor.” Based in Seattle, World Vision has a Rotarian, Brian Gower, on their staff as Rotary liaison.

Sim makes another crucial point: consult the people for whom the toilets are intended – the stakeholders most directly concerned. A solution that ignores their perspectives will be a tragic waste of time and money. Sim shared several stories of splendid new toilet blocks put to completely different uses. A school principal turned one into his office because he thought it was too fine for students to use.

Rotarians can get this right. Clayton Lee reports this story from the second global grant WASH project his club was partnering on in Honduras: “The host club was talking to the people in the village while the project was getting started and they were so impressed with Rotary that they started their own Rotary club. I know of no other story like this where the people served wanted to give back and started a new club.”

Credit: WTO 20th Anniversary Report. Enjoy the movie at mrtoiletmovie.com.

Jack Sim retired from his business career at age 40 and has been volunteering ever since. He is an Ashoka Fellow who has received multiple international awards as a social entrepreneur, including being named one of the 2008 Time Magazine Heroes of the Environment and receiving a 2018 Commonwealth Points of Light Award from Queen Elizabeth. He mounted a multi-year campaign to persuade the United Nations to designate a World Toilet Day (Nov. 19) to put a spotlight on the huge humanitarian need addressed by SDG #6.

I asked Sim if he is a Rotarian – he laughed and said he’s too busy to go to meetings, but has had ample opportunity to watch us in action and was given a Paul Harris fellowship by a Brazilian club along the way. He gave a speech at RI’s International Convention in Sydney and advocated for his home town Singapore to host RICON in 2024.

We dove into a discussion of how well Rotary projects fit the Four-Way Test. “Whose truth?” Sim asked, “yours or the beneficiary’s? Are you listening to him or telling him what is true? Who is ‘all concerned?’ How about ‘good well and better friendship:’ is the project condescending?”

He challenges Rotarians to get beyond our culture of being do-gooders and looking for instant gratification. “Is the mission about you or about the people? If you want to buy their poverty, the poor will sell it to you. Make the project less about you, and mainly about the people, then the way you behave will be totally different. Rotarians have good intentions, but it’s time to make all the good intentions of little, little projects into an ecosystem.”

Two metaphors: the Swiss watch and the thriving forest

“Poverty is caused by inefficiency,” Sim says. “Think of poverty as the components of a disassembled Swiss watch, and prosperity where all the pieces are working in synch with each other. In the real world, someone has taken the watch apart. All the components are there, but someone has scattered the pieces across the table. We want the watch to work, and we can put it back together. Every poverty problem in the world has been solved by someone somewhere. As Bill Clinton told me in 2011, we need to collate those solutions. We need a core team of people in Rotary who are thinking system change.

“We need to move from consumption growth economics – which is going to kill us – to a forest economy where nothing is wasted,” he adds. “Everything alive there is selfish, but the way they work together becomes selfless, creating the ability to sustain all the other life forms. Shit sustains the plants which feed the animals, who shit in turn. The accounting system is so ubiquitous that you don’t even keep track.”

In the human economic ecosystem, “you have to incentivize everyone and not moralize,” Sim adds. “If you moralize, you start to alienate people. Are you going to refuse to deal with a politician because he’s corrupt?” This points back to the Brazilian example, where advocates pointed out the benefits to each stakeholder – including politicians – of removing roadblocks to sanitation solutions. “Rotarians want to be benefactors,” he adds, “not to end poverty. Is my image more important than whether people get out of poverty?”

Can we end poverty?

Singapore’s story is proof that it’s possible. Sim was born to an impoverished family in Singapore in 1957, when most residents lacked safe water and many neighborhoods had no alternative to defecating outdoors or putting night soil out in the street. Deadly outbreaks of cholera and typhoid ravaged the population. He spent his childhood suffering from worms and diarrhea.

The city of his childhood was “poor, uneducated, corrupt, with lots of criminals,” he reports, indistinguishable from other Asian cities plagued with poverty and disease. But as Singapore emerged from British colonial rule in the 1960’s, its citizens and government took on a seemingly impossible goal: “one day in the distant future we wanted to reach the Swiss standard of living,” says Sim.

The entrepreneurial spirit of Singaporeans led them to seek out investment partners who could benefit from their superb deepwater port. Cleaning up the streets and ending the stink of untreated sewage was vital to attracting foreign investment. The city undertook a ten-year campaign to dredge the Singapore River and develop state-of-the-art water treatment. Sim’s contribution was to organize the Restroom Association of Singapore to build modern public toilets, engage the population so they would take pride in this infrastructure and care for it, to create institutions providing professional training for sanitation workers, and to advocate for them to be well-paid.

Today, within just a few decades, Singaporeans enjoy the fifth-highest income per capita in the world.

So, like the parties at COP, let’s look at our ambition, and aim high!