By Ariel Miller, ESRAG Newsletter Editor

Combating Malnutrition and Poverty with Semilla Nueva’s Biofortified Seeds

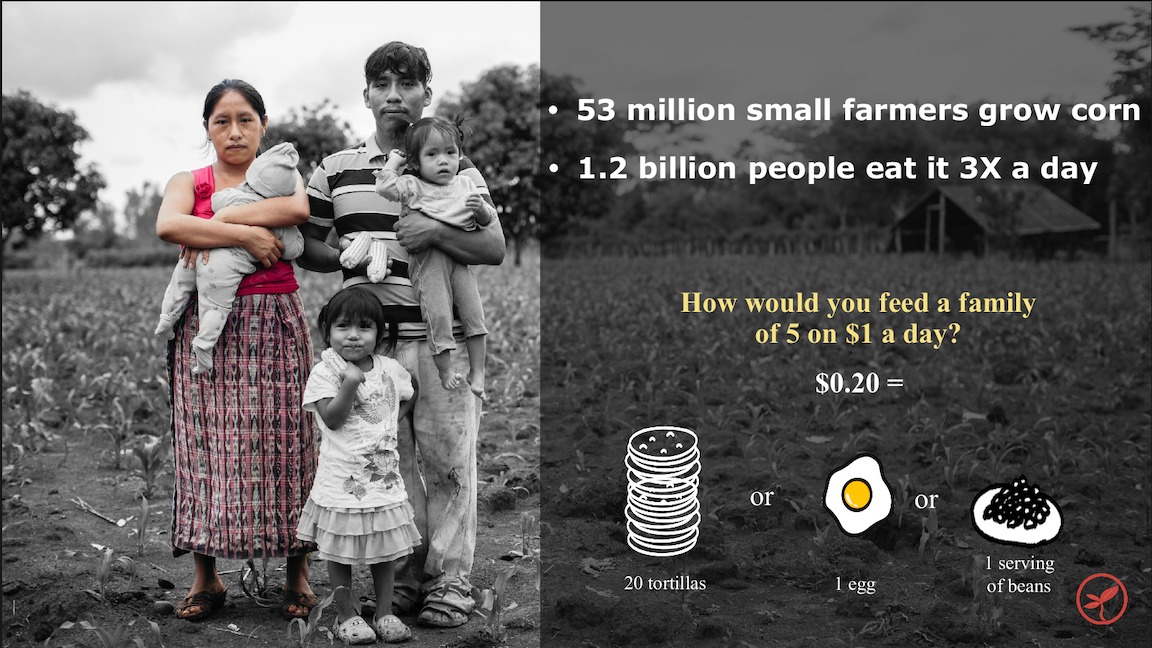

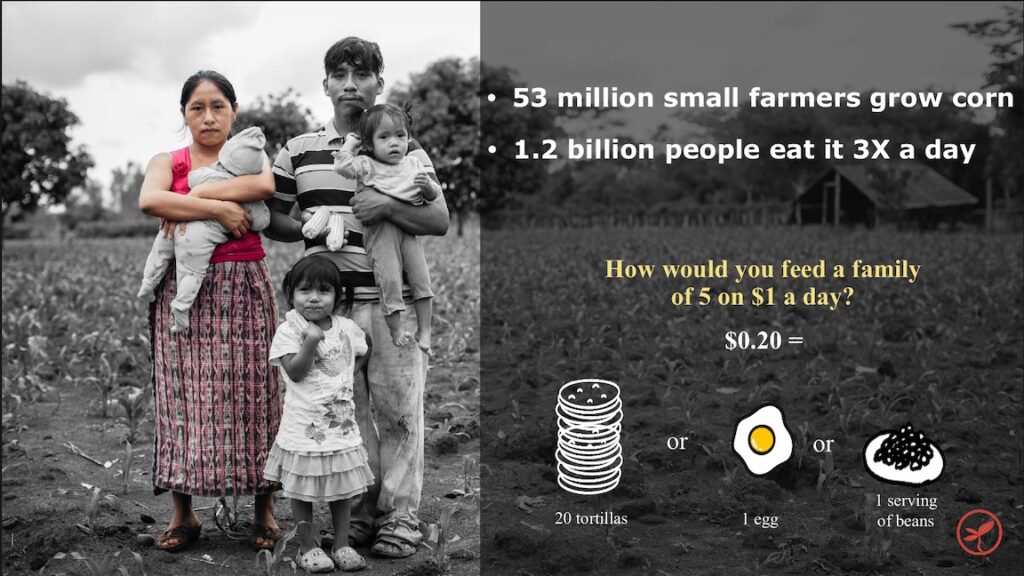

Trekking through the Guatemala highlands in his early twenties, meeting and listening to indigenous farmers, Curt Bowen was appalled to witness widespread malnutrition. The corn these farmers raised was nutritionally inadequate to prevent stunting, with lifelong harm to children’s physical and cognitive abilities, and its low yields trapped farmers in a cycle of poverty. Bowen embarked on a quest to empower farmers to fill that nutritional void and improve global nutrition. It’s urgent because 1.2 billion people worldwide depend on corn as their staple food.

The solution Bowen ultimately developed is Semilla Nueva (New Seed), a Guatemala-based US nonprofit with a scalable solution for making biofortified, climate-resilient, high-yield seed available to small farmers. With it, participating small farms are now raising corn that delivers zinc, iron, and quality protein—all essential to human health. The Semilla Nueva team is now preparing to expand its reach in Central America and East Africa. Semilla Nueva was chosen from 5,000 applicants as a finalist in the 2023 Zayed Sustainability Prize awarded at COP 28 in Dubai.

The son of ESRAG Communications Director Laurie Zuckerman, Bowen was encouraged and mentored by Idaho Rotarians as he developed the new nonprofit, and has worked with Rotary clubs on a series of grants, the most recent being a 2020-22 global grant for the Rotary Club of Guatemala de Ermita and RC Boise Southwest.

Rotary values front-and-centre

Semilla Nueva’s story exemplifies the qualifications Rotarians should look for in an NGO to help clubs achieve lasting humanitarian benefits: a team with proven technical expertise, whose members are rooted in the culture and economy, alert to the strengths of potential partners, and skilled in building win-win collaborations.

In 30 years of experience in Central America, I have never seen a nonprofit like this, from the big, unwieldy ones to small, earnest ones,” says Peace Corps alumnus Richard Knab, who recently joined Semilla Nueva as development director. “Its strength is a reliance on facts and numbers to make course corrections when needed while remaining laser-focused on what it does best.

In Guatemala, at present, almost 85% of corn farmers – who produce over half the maize consumed in the country – can’t afford improved seed, and instead depend on low-yield heirloom seeds. The research to develop biofortified hybrids is costly.

“Seeds need to be better, and farmers need to be able to afford them,” Knab explains.

Curt Bowen, the founder of Semilla Nueva

Shifting Focus to Enhance Seed Accessibility and Market Efficiency

Semilla Nueva went through several iterations including an early phase during which it promoted other nutritious crops, and more recently, a period during which it saw its role as that of a seed company, but Bowen “came to realize that existing local seed companies could take care of production and sales,” says Knab, “so Semilla Nueva is phasing out its seed production to focus on breeding and working with governments on subsidies, thus helping the market to work better.” Here’s how the NGO closes gaps so biofortified seed reaches those who urgently need it.

- Building on years of research and field testing by the scientific community, Semilla Nueva is breeding new corn hybrids with the traits needed in the target regions.

- Semilla Nueva provides the parent seed for these new strains for free to partner seed companies and pays the companies a small subsidy so they can produce and sell the biofortified seed at prices affordable to subsistence farmers.

- Semilla Nueva works with governments, encouraging them to fund and co-manage these subsidies on a national scale.

Semilla Nueva tackling Global Nutrition

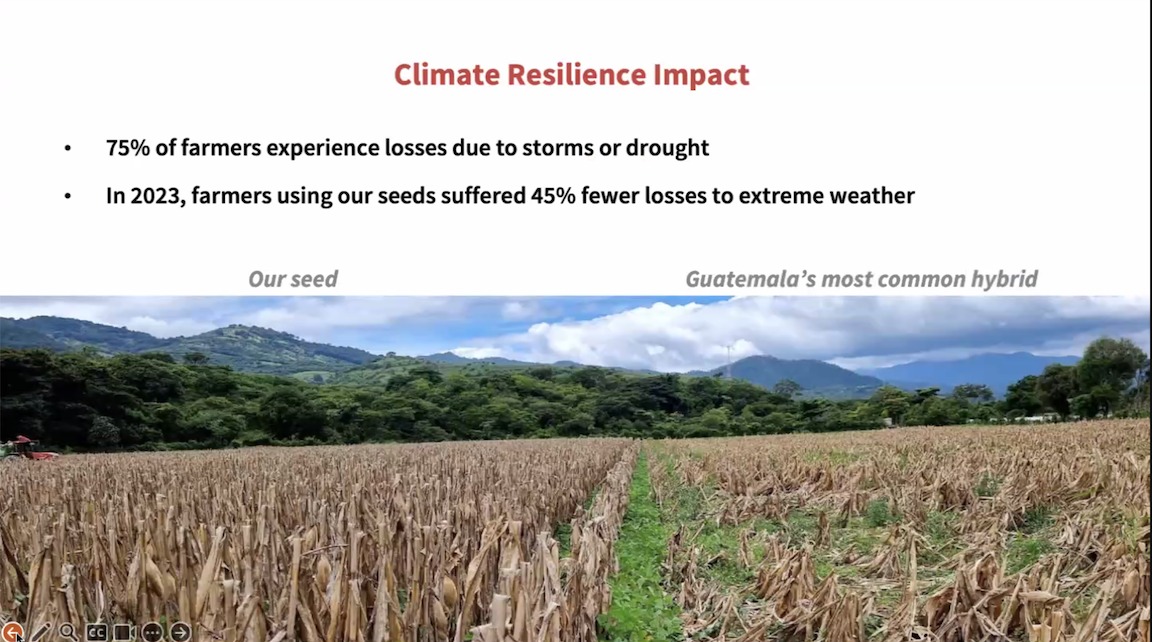

Third-party studies have documented that the new biofortified corn hybrids bring significant improvements in health, climate resilience, and farmers’ income. A Harvard meta-analysis showed declines of up to 20% in child stunting among children eating biofortified corn. While 75% of Guatemalan farmers suffered crop losses in 2023 due to drought or storms, farmers using Semilla Nueva seeds reported 45% fewer losses due to extreme weather. Participating farmers earned from 35% to 115% more, enabling them to afford life-changing investments like tuition for their children and labor-saving equipment for their farms.

75% of Semilla Nueva’s work is funded by private grants and donations, and 20% from foreign aid (such as USAID). “Semilla Nueva receives an extraordinarily high proportion of unrestricted funding from family foundations who invest in innovative CEOs with scalable solutions,” Knab says. “Relationships are really important.”

The average subsidy needed per farmer in Guatemala is $19 per crop cycle.

According to Knab,

Biofortified corn is a cost-efficient solution to malnutrition and poverty, and our seeds are extremely popular among farmers. If seed subsidies become government policy, they can generate a lot of votes in rural areas!

Semilla Nueva’s Journey to Transform Global Nutrition

Since its inception, Semilla Nueva’s reach has grown rapidly, from a few thousand farmers in 2018 to over 24,000 farmers who collectively fed 800,000 people in Guatemala in 2023. About 3% of the country’s maize crop was biofortified that year, but Semilla Nueva has set a long-term goal of raising that proportion to 50%.

Bowen’s team are launching a pilot program with the government of El Salvador in 2024. They have begun the research and testing to expand to Honduras in 2025 and, eventually, to corn-staple societies in Sub-Saharan Africa, to equip 3 million farmers to improve the nutrition of 100 million people by 2036.

Climate Resilience Impact

Semilla Nueva’s ability to scale up the impact got a huge boost in February of 2024. Collaborating with scientists at the University of Wisconsin, Semilla Nueva’s research team is starting to use CRISPR gene editing with the potential to reduce the time needed to develop a successful new hybrid, from four to six years and a cost as high as $300,000, to one year and $30,000.

Gene editing could be a real game-changer for us, making it possible to quickly and inexpensively biofortify the best possible seed for any location in the world, Bowen writes.

Enrique Kreff, Semilla Nueva’s Breeding Director, adds that the gene editing involves minor modifications and the resulting seeds will be considered non-GMO.

In addition to Semilla Nueva’s achievement in being a finalist for the Zayed Sustainability Prize, Bowen was honoured as one of Forbes’ 30 under 30, a Mulago Fellow, and an Ashoka Fellow. It’s a wonderful trajectory for a farm boy raised in Idaho in a multigenerational Rotary family. Most exciting of all is the realistic hope that his NGO will be able to empower millions of farmers to increase their incomes, withstand climate change, overcome malnutrition, and contribute to global nutrition.

Graphics: Semilla Nueva